The Camera

As mentioned in Section 8.1.1, in rendering we compute the radiance from the shaded surface point to the camera position. This simulates a simplified model of an imaging system such as a film camera, digital camera, or human eye.

Such systems contain a sensor surface composed of many discrete small sensors. Examples include rods and cones in the eye, photodiodes in a digital camera, or dye particles in film. Each of these sensors detects the irradiance value over its surface and produces a color signal. Irradiance sensors themselves cannot produce an image, since they average light rays from all incoming directions. For this reason, a full imaging system includes a light-proof enclosure with a single small aperture (opening) that restricts the directions from which light can enter and strike the sensors. A lens placed at the aperture focuses the light so that each sensor receives light from only a small set of incoming directions. The enclosure, aperture, and lens have the combined effect of causing the sensors to be directionally specific. They average light over a small area and a small set of incoming directions. Rather than measuring average irradiance-which as we have seen in Section 8.1.1 quantifies the surface density of light flow from all directions-these sensors measure average radiance, which quantifies the brightness and color of a single ray of light.

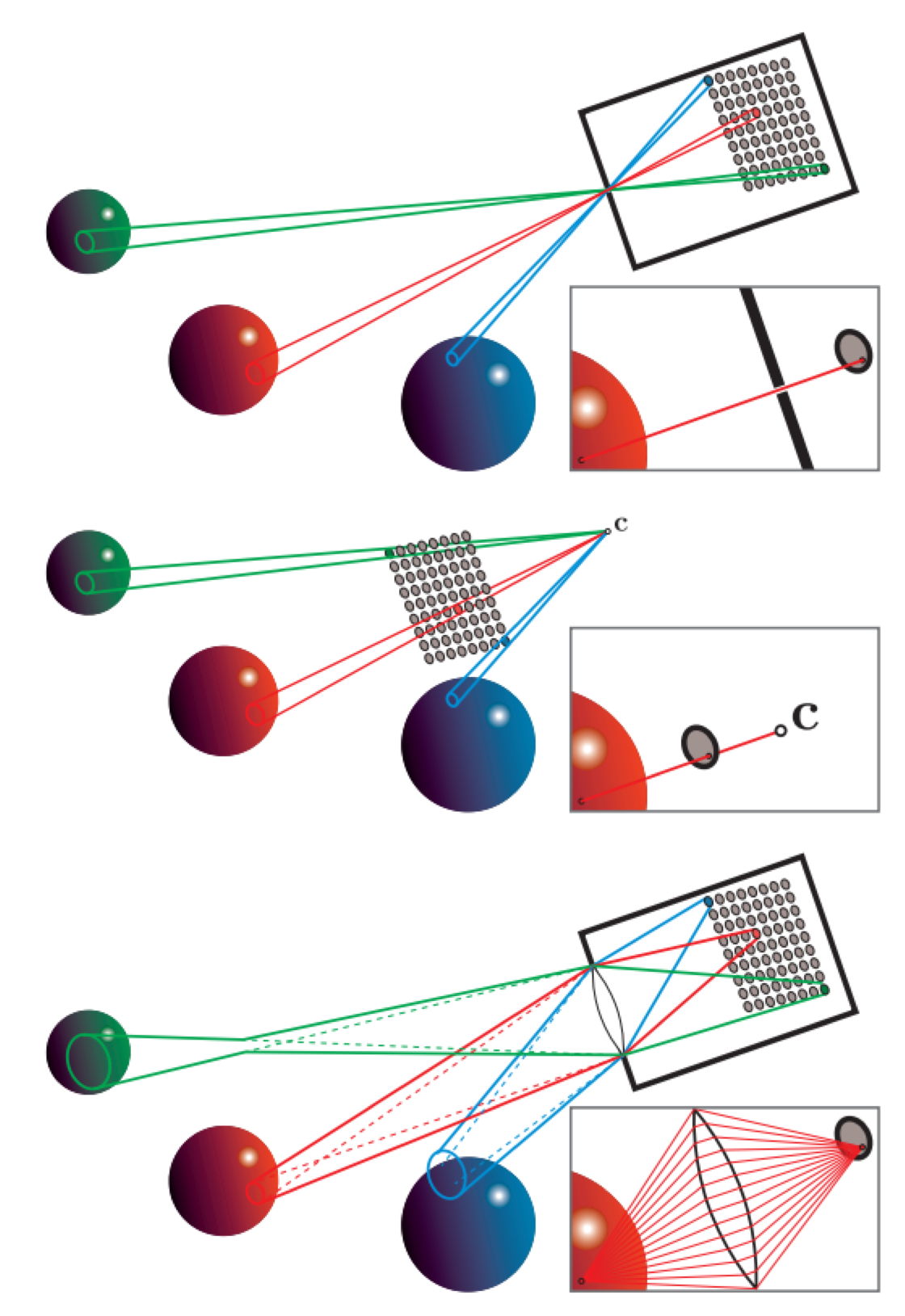

Figure 9.16: Each of these camera model figures contains an array of pixel sensors. The solid lines bound the set of light rays collected from the scene by three of these sensors. The inset images in each figure show the light rays collected by a single point sample on a pixel sensor. The top figure shows a pinhole camera, the middle figure shows a typical rendering system model of the same pinhole camera with the camera point c, and the bottom figure shows a more physically correct camera with a lens. The red sphere is in focus, and the other two spheres are out of focus.

Historically, rendering has simulated an especially simple imaging sensor called a pinhole camera, shown in the top part of Figure 9.16. A pinhole camera has an extremely small aperture-in the ideal case, a zero-size mathematical point-and no lens. The point aperture restricts each point on the sensor surface to collect a single ray of light, with a discrete sensor collecting a narrow cone of light rays with its base covering the sensor surface and its apex at the aperture. Rendering systems model pinhole cameras in a slightly different (but equivalent) way, shown in the middle part of Figure 9.16. The location of the pinhole aperture is represented by the point $c$, often referred to as the “camera position” or “eye position.” This point is also the center of projection for the perspective transform (Section 4.7.2).

When rendering, each shading sample corresponds to a single ray and thus to a sample point on the sensor surface. The process of antialiasing (Section 5.4) can be interpreted as reconstructing the signal collected over each discrete sensor surface. However, since rendering is not bound by the limitations of physical sensors, we can treat the process more generally, as the reconstruction of a continuous image signal from discrete samples.

Although actual pinhole cameras have been constructed, they are poor models for most cameras used in practice, as well as for the human eye. A model of an imaging system using a lens is shown in the bottom part of Figure 9.16. Including a lens allows for the use of a larger aperture, which greatly increases the amount of light collected by the imaging system. However, it also causes the camera to have a limited depth of field (Section 12.4), blurring objects that are too near or too far.

The lens has an additional effect aside from limiting the depth of field. Each sensor location receives a cone of light rays, even for points that are in perfect focus. The idealized model where each shading sample represents a single viewing ray can sometimes introduce mathematical singularities, numerical instabilities, or visual aliasing. Keeping the physical model in mind when we render images can help us identify and resolve such issues.