Shadow Volumes

Method Overview

A method based on shadow volumes can cast shadows onto arbitrary objects by clever use of the stencil buffer. It can be used on any GPU, as the only requirement is a stencil buffer. It is not image based (unlike the shadow map algorithm described next) and so avoids sampling problems, thus producing correct sharp shadows everywhere. This can sometimes be a disadvantage. For example, a character’s clothing may have folds that give thin, hard shadows that alias badly. Shadow volumes are rarely used today, due to their unpredictable cost.

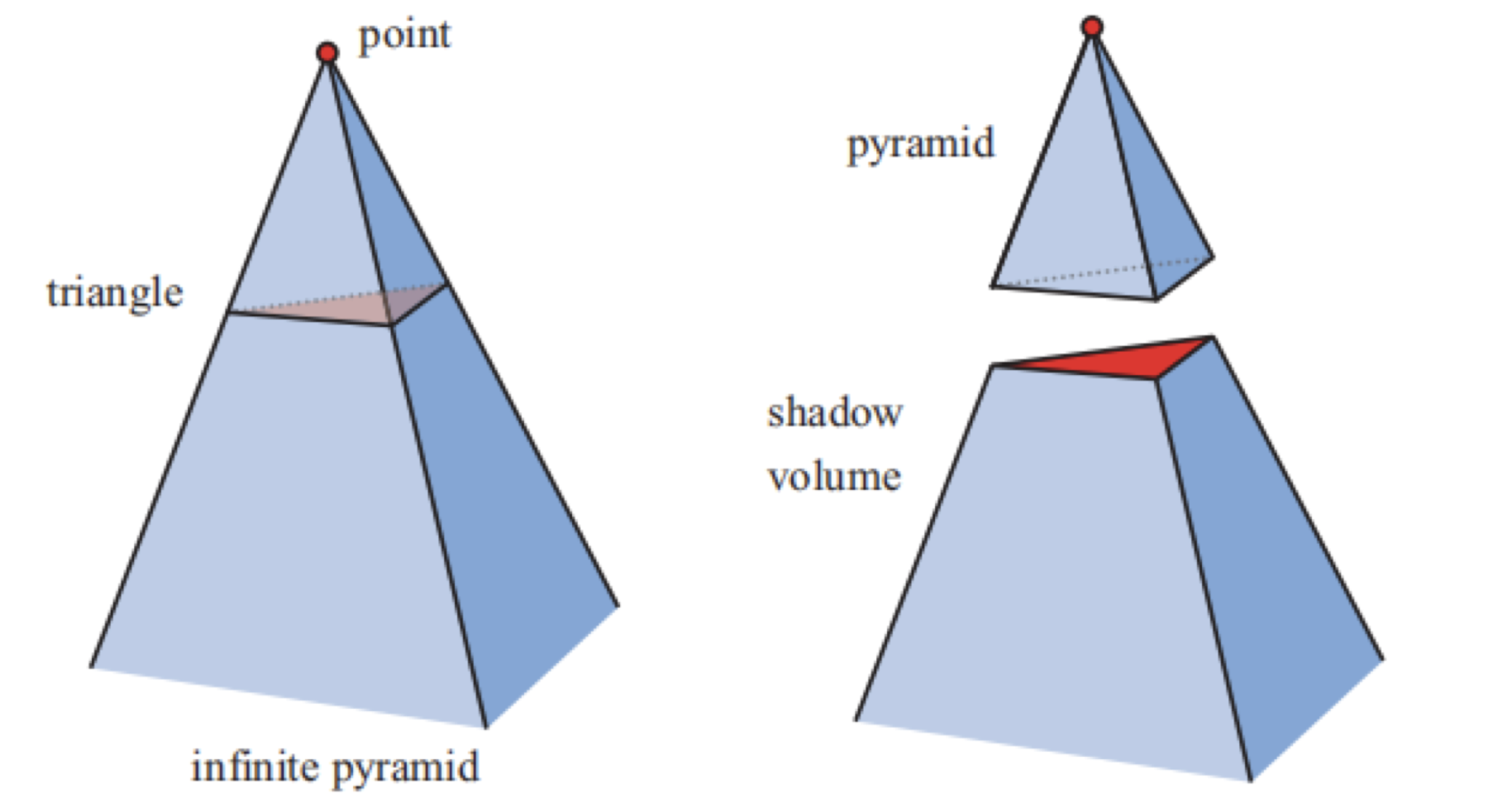

To begin, imagine a point and a triangle. Extending the lines from a point through the vertices of a triangle to infinity yields an infinite three-sided pyramid. The part under the triangle, i.e., the part that does not include the point, is a truncated infinite pyramid, and the upper part is simply a pyramid. Now imagine that the point is actually a point light source. Then, any part of an object that is inside the volume of the truncated pyramid (under the triangle) is in shadow. This volume is called a shadow volume.

Say we view some scene and follow a ray from the eye through a pixel until the ray hits the object to be displayed on screen. While the ray is on its way to this object, we increment a counter each time it crosses a face of the shadow volume that is frontfacing (i.e., facing toward the viewer). Thus, the counter is incremented each time the ray goes into shadow. In the same manner, we decrement the same counter each time the ray crosses a backfacing face of the truncated pyramid. The ray is then going out of a shadow. We proceed, incrementing and decrementing the counter until the ray hits the object that is to be displayed at that pixel. If the counter is greater than zero, then that pixel is in shadow; otherwise it is not. This principle also works when there is more than one triangle that casts shadows.

A two-dimensional side view of counting shadow-volume crossings using two different counting methods. In z-pass volume counting, the count is incremented as a ray passes through a frontfacing triangle of a shadow volume and decremented on leaving through a backfacing triangle. So, at point A, the ray enters two shadow volumes for +2, then leaves two volumes, leaving a net count of zero, so the point is in light. In z-fail volume counting, the count starts beyond the surface (these counts are shown in italics). For the ray at point B, the z-pass method gives a +2 count by passing through two frontfacing triangles, and the z-fail gives the same count by passing through two backfacing triangles. Point C shows how z-fail shadow volumes must be capped. The ray starting from point C first hits a frontfacing triangle, giving ?1. It then exits two shadow volumes (through their endcaps, necessary for this method to work properly), giving a net count of +1. The count is not zero, so the point is in shadow. Both methods always give the same count results for all points on the viewed surfaces.

Doing this with rays is time consuming. But there is a much smarter solution : A stencil buffer can do the counting for us.

- First, the stencil buffer is cleared.

- Second, the whole scene is drawn into the framebuffer with only the color of the unlit material used, to get these shading components in the color buffer and the depth information into the z-buffer.

- Third, z-buffer updates and writing to the color buffer are turned off (though z-buffer testing is still done), and then the frontfacing triangles of the shadow volumes are drawn. During this process, the stencil operation is set to increment the values in the stencil buffer wherever a triangle is drawn.

- Fourth, another pass is done with the stencil buffer, this time drawing only the backfacing triangles of the shadow volumes. For this pass, the values in the stencil buffer are decremented when the triangles are drawn. Incrementing and decrementing are done only when the pixels of the rendered shadow-volume face are visible (i.e., not hidden by any real geometry). At this point the stencil buffer holds the state of shadowing for every pixel.

- Finally, the whole scene is rendered again, this time with only the components of the active materials that are affected by the light, and displayed only where the value in the stencil buffer is 0. A value of 0 indicates that the ray has gone out of shadow as many times as it has gone into a shadow volume?i.e., this location is illuminated by the light.

This counting method is the basic idea behind shadow volumes. There are efficient ways to implement the algorithm in a single pass. However, counting problems will occur when an object penetrates the camera’s near plane. The solution, called z-fail, involves counting the crossings hidden behind visible surfaces instead of in front.

Method Drawback

Creating quadrilaterals for every triangle creates a huge amount of overdraw. That is, each triangle will create three quadrilaterals that must be rendered. A sphere made of a thousand triangles creates three thousand quadrilaterals, and each of those quadrilaterals may span the screen. One solution is to draw only those quadrilaterals along the silhouette edges of the object, e.g., our sphere may have only fifty silhouette edges, so only fifty quadrilaterals are needed. The geometry shader can be used to automatically generate such silhouette edges. Culling and clamping techniques can also be used to lower fill costs.

However, the shadow volume algorithm still has a terrible drawback: extreme variability. Imagine a single, small triangle in view. If the camera and the light are in exactly the same position, the shadow-volume cost is minimal. The quadrilaterals formed will not cover any pixels as they are edge-on to the view. Only the triangle itself matters. Say the viewer now orbits around the triangle, keeping it in view. As the camera moves away from the light source, the shadow-volume quadrilaterals will become more visible and cover more of the screen, causing more computation to occur. If the viewer should happen to move into the shadow of the triangle, the shadow volume will entirely fill the screen, costing a considerable amount of time to evaluate compared to our original view. This variability is what makes shadow volumes unusable in interactive applications where a consistent frame rate is important. Viewing toward the light can cause huge, unpredictable jumps in the cost of the algorithm, as can other scenarios.

For these reasons shadow volumes have been for the most part abandoned by applications. However, given the continuing evolution of new and different ways to access data on the GPU, and the clever repurposing of such functionality by researchers, shadow volumes may someday come back into general use.