Display Encoding

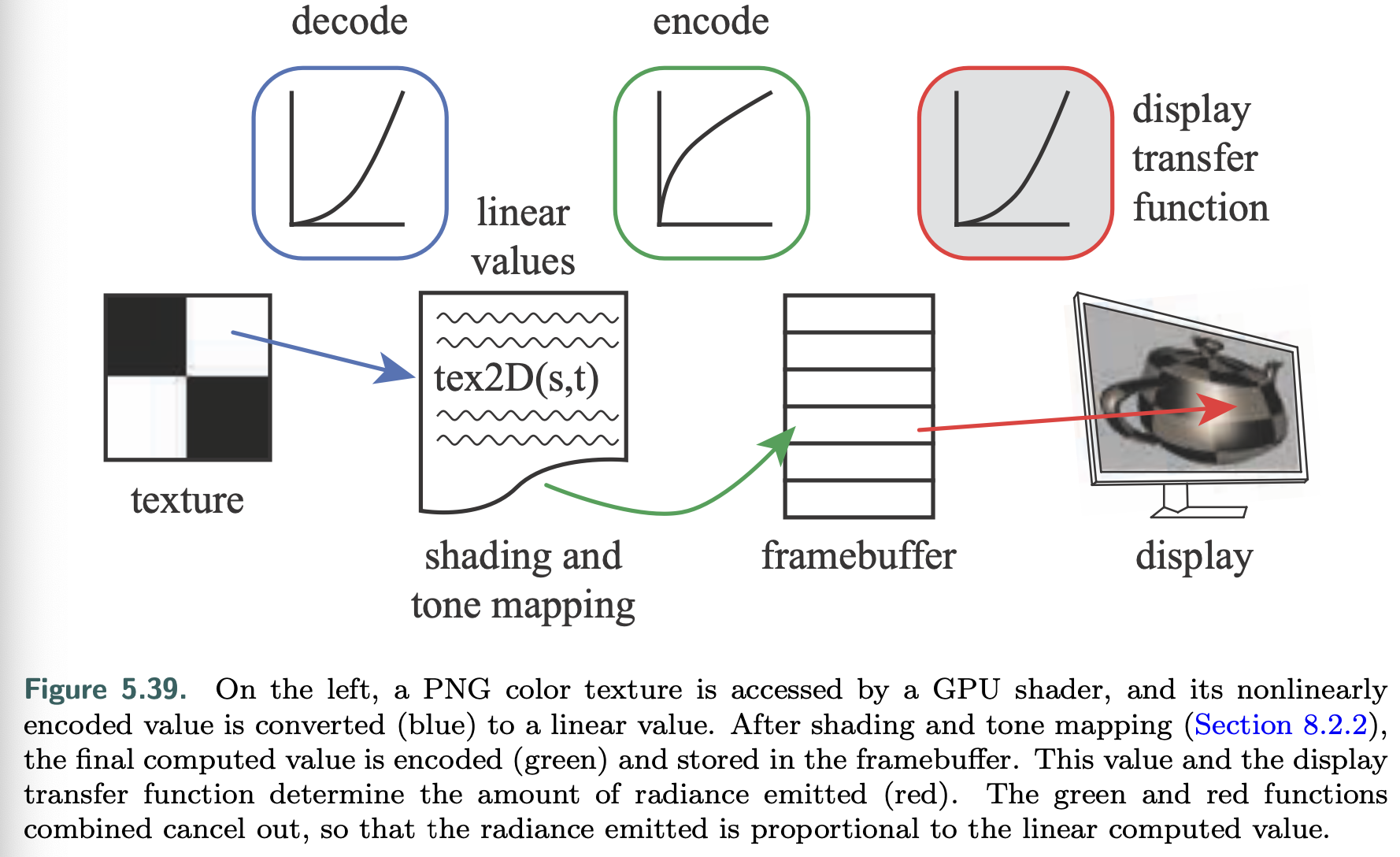

When we calculate the effect of lighting, texturing, or other operations, the values used are assumed to be linear. However, to avoid a variety of visual artifacts, display buffers and textures use nonlinear encodings that we must take into account.

In most cases you can tell the GPU to do gamma correction for you.

Why Gamma Correction?

Display devices (CRT) exhibit a power law relationship between input voltage and display radiance. As the energy level applied to a pixel is increased, the radiance emitted does not grow linearly but (surprisingly) rises proportional to that level raised to a power greater than one.

This power function nearly matches the inverse of the lightness sensitivity of human vision.

The consequence of this fortunate coincidence is that the encoding is roughly perceptually uniform. That is, the perceived difference between a pair of encoded values N and N + 1 is roughly constant over the displayable range. Measured as threshold contrast, we can detect a difference in lightness of about 1% over a wide range of conditions.

This near-optimal distribution of values minimizes banding artifacts when colors are stored in limited-precision display buffers (Section 23.6). The same benefit also applies to textures, which commonly use the same encoding.

The display transfer function describes the relationship between the digital values in the display buffer and the radiance levels emitted from the display. For this reason it is also called the electrical optical transfer function (EOTF). The display transfer function is part of the hardware, and there are different standards for computer monitors, televisions, and film projectors. There is also a standard transfer function for the other end of the process, image and video capture devices, called the optical electric transfer function (OETF).

When encoding linear color values for display, our goal is to cancel out the effect of the display transfer function, so that whatever value we compute will emit a corresponding radiance level. To maintain this connection, we apply the inverse of the display transfer function to cancel out its nonlinear effect. This process of nullifying the display’s response curve is also called gamma correction. When decoding texture values, we need to apply the display transfer function to generate a linear value for use in shading.

The standard transfer function for personal computer displays is defined by a color-space specification called sRGB. Most APIs controlling GPUs can be set to automatically apply the proper sRGB conversion when values are read from textures or written to the color buffer.

As discussed in Section 6.2.2, mipmap generation will also take sRGB encoding into account. Bilinear interpolation among texture values will work correctly, by first converting to linear values and then performing the interpolation. Alpha blending is done correctly by decoding the stored value back into linear values, blending in the new value, and then encoding the result.

It is important to apply the conversion at the final stage of rendering, when the values are written to the framebuffer for the display. If post-processing is applied after display encoding, such effects will be computed on nonlinear values, which is usually incorrect and will often cause artifacts.

Display encoding can be thought of as a form of compression, one that best preserves the value’s perceptual effect.

Manual sRGB Apply

In practical terms the display is controlled by a number of bits per color channel, e.g., 8 for consumer-level monitors, giving a set of levels in the range [0,255]. Here we express the display-encoded levels as a range [0.0,1.0], ignoring the number of bits. The linear values are also in the range [0.0, 1.0], representing floating point numbers.

We denote these linear values by x and the nonlinearly encoded values stored in the framebuffer by y. So the inverse of the sRGB display transfer function is:

\[y=f_{sRGB}^{-1}(x)=1.055x^{1/2.4}-0.055,where\ x>0.0031308\] \[=12.92x, where\ x\leq0.0031308\]One source of error is using an encoded color instead of its linear form, and another is decoding or encoding a color twice.

With the offset and scale taken into account, this function closely approximates a simpler formula: \(y=f_{display}^{-1}(x)=x^{1/\gamma}, \gamma = 2.2\)

Sometimes you will see a conversion pair that is simpler still, particularly on mobile and browser apps:

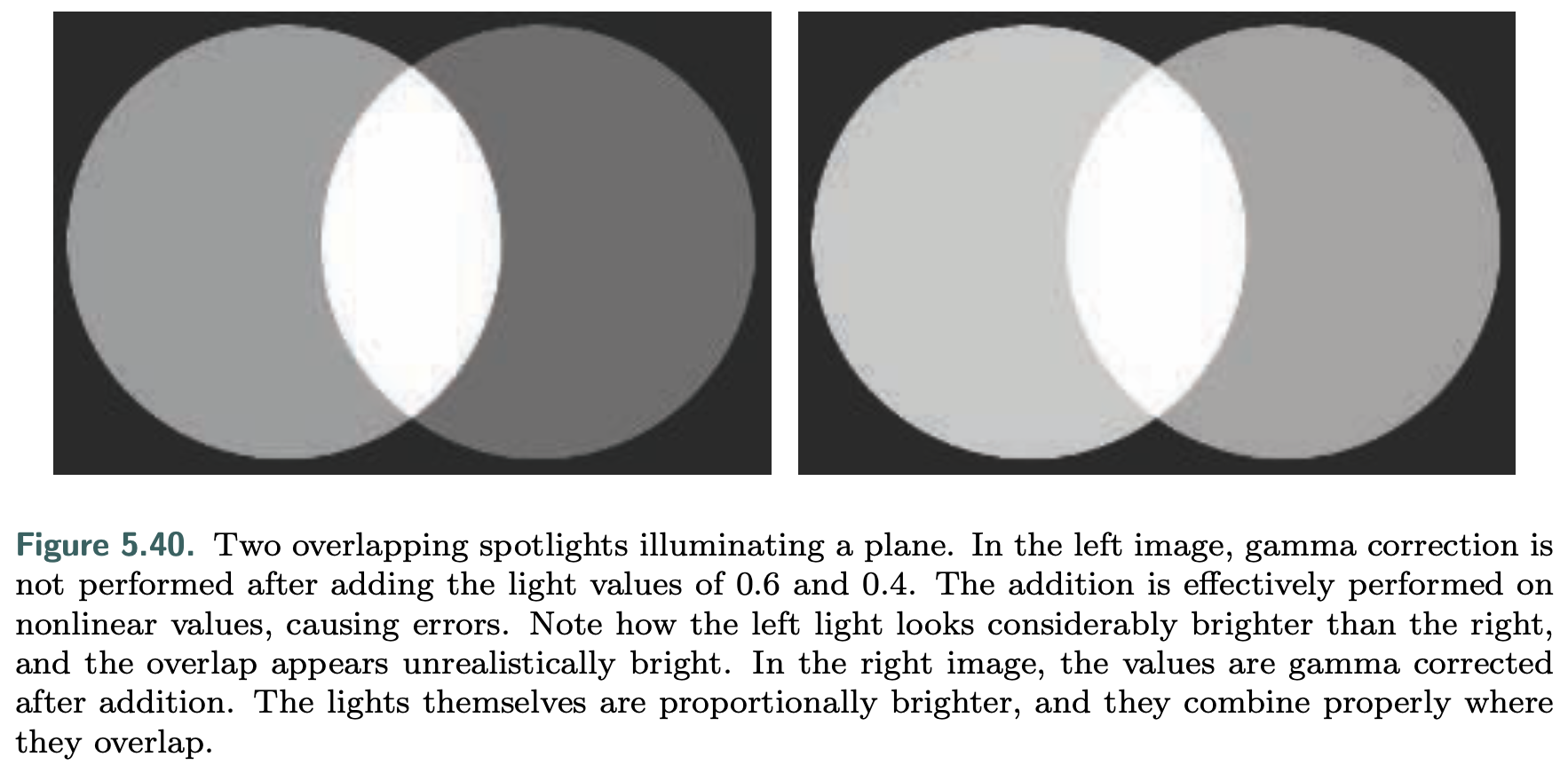

\[y=f_{simpl}^{-1}(x)=\sqrt{x}\] \[x=f_{simpl}(x)=y^2\]If we do not pay attention to gamma, lower linear values will appear too dim on the screen. A related error is that the hue of some colors can shift if no gamma correction is performed. Another problem with neglecting gamma correction is that shading computations that are correct for physically linear radiance values are performed on nonlinear values.

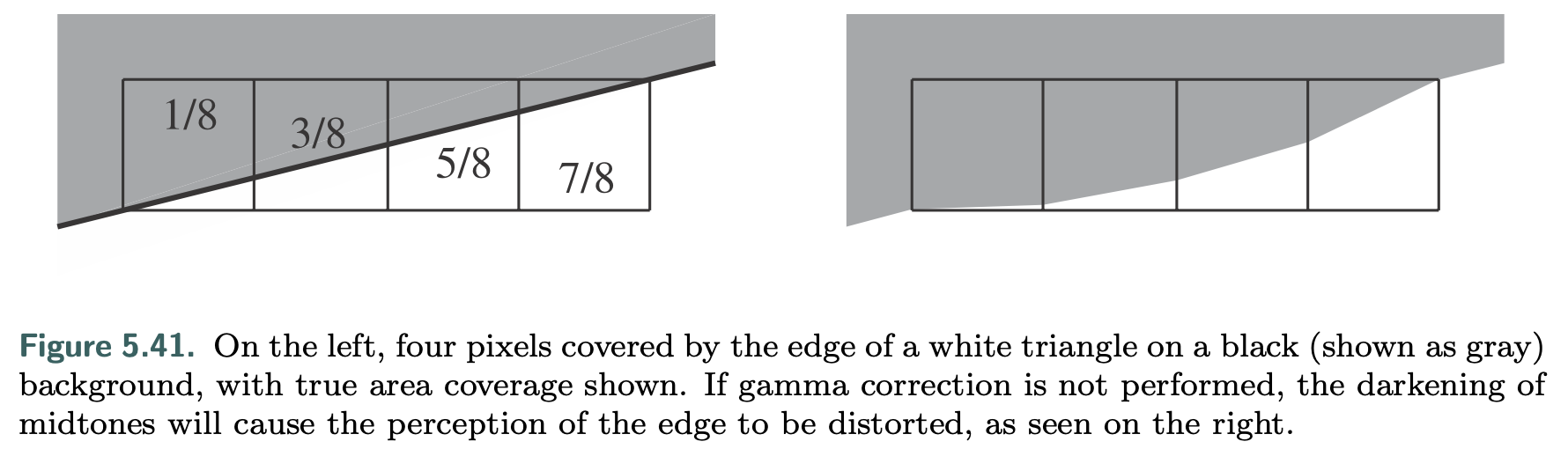

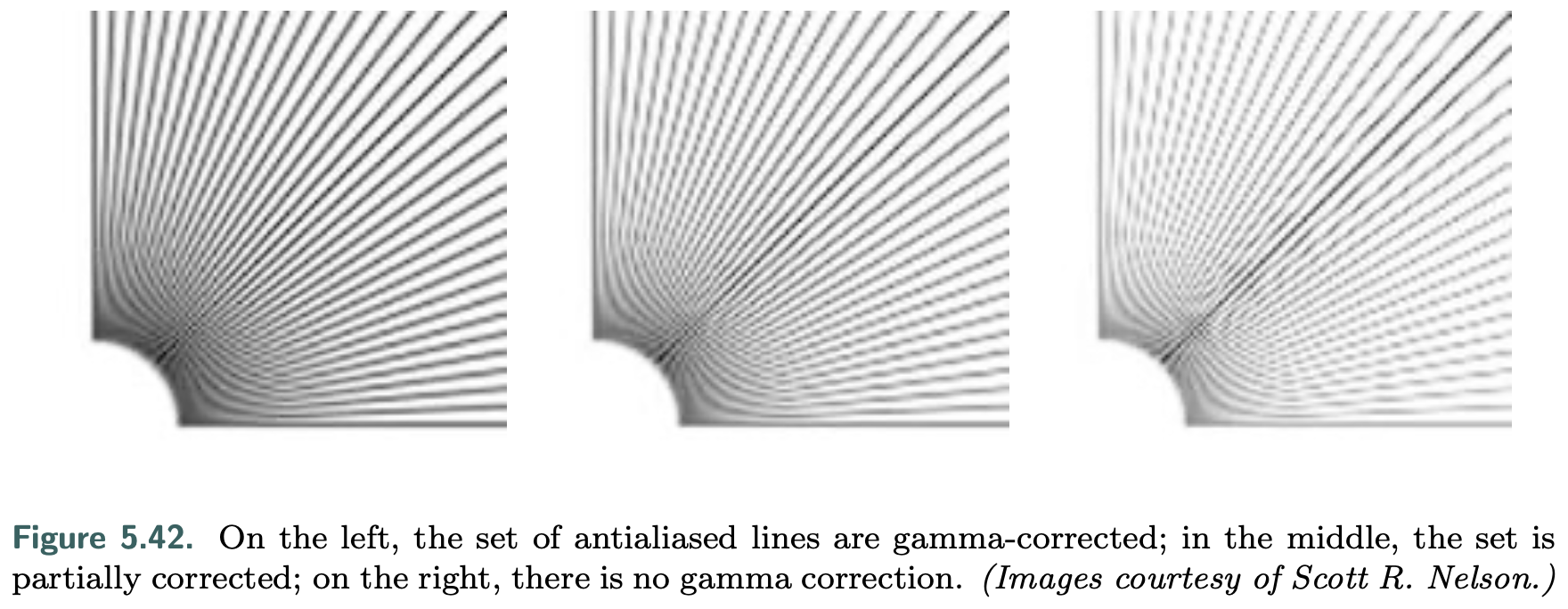

Ignoring gamma correction also affects the quality of antialiased edges.

If this is not done, the represented radiance for the pixels will be too dark, resulting in a perceived deformation of the edge as seen in the right side of the figure. This artifact is called roping, because the edge looks somewhat like a twisted rope.

Ignoring gamma correction also affects the quality of antialiased edges.

Monitors that are brighter and that can display a wider range of colors have been developed. Color display and brightness are discussed in Section 8.1.3, and display encoding for high dynamic range displays is presented in Section 8.2.1.